“The play is presented as a rehearsal and takes place on a bare stage against a neutral backdrop, with perhaps one or two masking legs on either side.

During the play the facade of the White House as it changes through the years appears in the dark behind the drop as if suspended in mid-air.

Whenever possible, the actors enter from and exit to rehearsal benches on either side of the stage.

The time of the rehearsal is the present.

The time of the play is 1792-1902.”

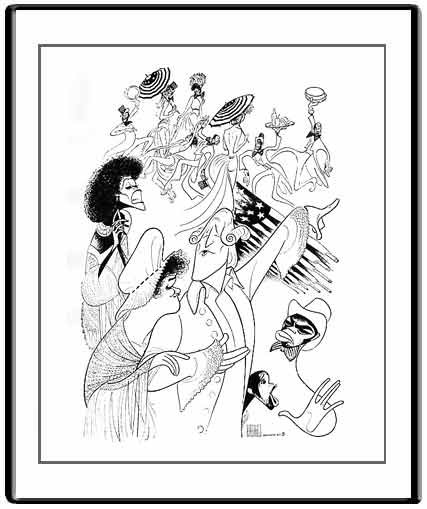

This is an excerpt from the first page of a 1975 draft of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, in which librettist and lyricist Alan Jay Lerner establishes his well-intentioned ideas for the show. It all sounds intriguing, but the final product ended up an unfortunate footnote in Broadway history. One hundred years of the White House and race relations, with a passing resemblance to Upstairs/Downstairs presented as a musical with music by Leonard Bernstein.

Why am I fascinated? Because there is so much that is good, but there is no clear execution of the underlying concept. Lerner wanted to use the conceit of the musical play being a show constantly in rehearsal, but there was so much history to cover that the concept muddied the presidential pageantry with what seemed like two or three different musicals happening at once. Lerner wanted the actors to step out and comment on the nation’s racial situation during and between scenes, but it was a promising idea left unfulfilled.

The draft contains many lines and situations which we will be a part of the final musical product (either in Philadelphia or New York). The through line for the family of servants is in place, as well as most of the presidents. Interestingly enough, there was a lot more material for the First Lady in the first version, but the “Duet for One” was not yet conceived. That moment was part of a transition song for the President to sing in the second act while talking to his servant Lud. His lyrics about the Hayes election were incorporated into the future showstopper, but glossed over many years of presidential history, turning events into soundbites.

Already there is trouble. How do you decide which presidents are the most important, especially in terms of racial America? And of course, what about the other troubles of the first hundred years of the White House? Washington appears at the top, skips Adams (leaving that scene for Abigail) into Jefferson without much in the way of lucid transition. It’s confusing just to read one scene go into the next, because the stage ideas are half-baked, musical numbers left unfinished – though there are some which were performed without any changes from this draft. Delving into various presidents, their relationships with the wives plus the household servants, there is little room for the theatrical metaphors, which get lost along the way and are brought up in arbitrary moments. It was in this part of the gestation that a call should have been made regarding whether or not the concept was even necessary. There are passing references to Mrs. Adams, who is easily the most fleshed out of the Presidents or First Ladies, becoming a ghost (!) but again, the ideas lack specificity. For what it’s worth though, the dialogue in this draft is better than most of the lines heard in the final Broadway version. Ultimately 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue became a Presidential revue masquerading as a serious musical play.

But for me it comes back to that score, with its brilliant use of American-sounding idioms and Leonard Bernstein’s variations on patriotic numbers (including citations from “Hail to the Chief,” “Yankee Doodle” and “To Anacreon in Heaven,” which was adapted for our National Anthem). The overture, which played on Broadway, is worthy of the concert stage. Bernstein creates an eclectic musical style, with marches, waltzes, cakewalk, calypso and even a minstrel show reflecting on or commenting on the relations between Black and White America. (The minstrel show was met with a chilly reception, apparently resulting in booing and walkouts, which is also why I’m curious to see The Scottsboro Boys). The whole enterprise is done in by the lofty ambitions of Lerner’s script, which was eviscerated by the time the show opened at the Mark Hellinger Theatre.

I do wish that one of these days, someone might (to steal from Hugh Wheeler) find a coherent existence after so many years of muddle. The show failed, the score was swept under a rug without a cast album. But there are folks who wouldn’t let it be forgotten. Tapes of the show from its various incarnations exist in certain circles, and provide interesting insight into the show that wasn’t there.

In 1997, A White House Cantata, a concert showcasing highlights from the score, was the final result of several attempts at revision. However, as I’ve stated before, I don’t feel that staid classical piece (which plays like a sung history lesson) should be the final word. I do wonder if the Bernstein and Lerner estates would be interested in ever resuscitating the original piece for a complete studio album – with Broadway actors. In spite of the critical response of ’76, what remains is the score. A CD is available of A White House Cantata featuring Thomas Hampson and June Anderson. Conducted without feeling by Kent Nagano, the item is really for serious collectors only. It’s drained of anything close to color and life, mired in classical pretensions (particularly whenever Anderson tries to be funny).

In related news, some numbers from the score have been published for the very first time. “Take Care of This House” was for many years the only song available. The vocal selections which were printed by the Music of the Times Publishing Corp. were available for a short period of time and while incredibly rare, copies are available for perusal in the NYPL stacks. However, the mammoth soprano showcase, “Duet for One” was not included. It is now available for all those daring sopranos out there, published this summer as part of the new three book collection “Bernstein Theatre Songs” (high voice selections). While Bernstein’s “Glitter and Be Gay” is a demanding coloratura aria, his “Duet for One” calls for more incisive acting as the soprano involved must create two specific characters, alternate between mezzo and soprano, and cap it off with a D above high C. It is a highly satisfying enterprise, particularly as performed by Patricia Routledge in the original production.

No amount of revision could make 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue a great musical, or even a functioning one, but it contains a score of considerable merit and one which I think all serious musical theatre fans should know.

This is wonderful ! Congratulations!

New York City Opera is doing a 2 nights of “Lucky to Be Me: The Music of Leonard Bernstein” that will include music from “1600” – Nov. 6/7. Single seats go on sale on 9/7.